Event-Driven Simulation

Simulators replicate computer chip behavior using software, requiring action-by-action recreation in chronological order for accurate behavior emulation. Effective time management is crucial in computer architecture simulators to advance the simulated environment's time appropriately. This ensures that instructions, events, and system state updates are logical and consistent, mirroring the behavior and timing of the target architecture.

Record time with floating point numbers.

In most simulators, time is typically recorded using unsigned 64-bit integers as a unit of cycles. These simulators report the number of cycles required for an application to run, which is generally sufficient for most cases. However, in Akita, we aim to provide a more generic and flexible approach.

There are several cases that need to be considered. First, the Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling (DVFS) feature allows the system's frequency to change dynamically. Second, some architectures have multiple frequency domains; cores and memory systems can run at different frequencies. In both cases, using integers to represent time can be more complex.

To simplify, we represent time as a floating-point number, using the type VTimeInSec (refer to the code below). "V" in this type stands for virtual time, which is different from real time. Virtual time refers to the time in the simulated world, whereas real time is the actual time elapsed in our world. For instance, if our simulator takes 1 hour to simulate a GPU executing a 1 ms application, the 1 hour is real time and 1 ms is virtual time. Additionally, "InSec" indicates that the time unit in Akita is consistently in seconds, eliminating confusion and miscommunication about the time unit.

type VTimeInSec float64

Frequency and clock cycles.

Digital circuit update their states at clock cycle boundaries (ticks). These clock cycles usually maintain a steady frequency, which defines how soon digital circuit can update their status. This requires the simulator keep needing to calculate the time of the next cycle boundary. To address the need, Akita provides a frequency type.

The frequency type is also simply an alias of float64 (see code below).

type Freq float64

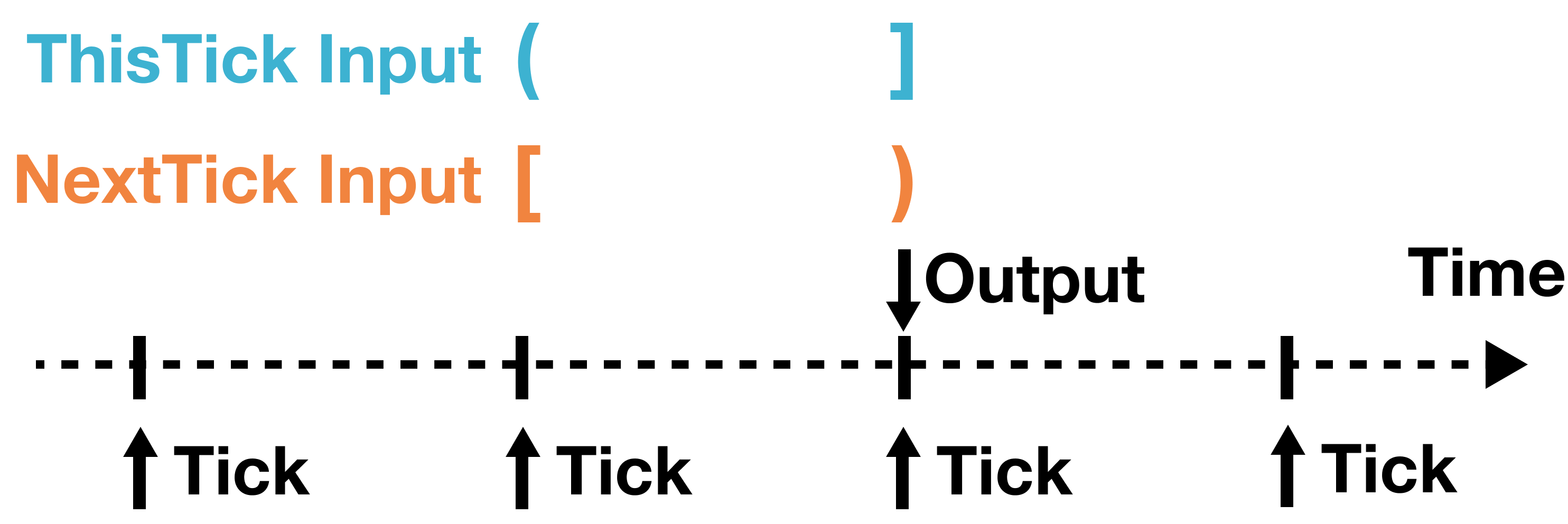

However, it provides a few utility functions that can perform commonly used calculations, including Period, ThisTick, and NextTick. Period returns the reciprocal of the frequency, representing the during between two cycle boundaries. ThisTick and NextTick both takes a time as input argument and return the cycle boundary time. ThisTick returns the earliest cycle boundary time that is equal or after the input time, while NextTick returns the earliest cycle boundary time that is after the input time. The only difference is that if the input time is right on a boundary, TickTick will return the input time, but NextTick will return the input time plus a period. The relationship is also depicted in the figure below.

func (f Freq) ThisTick(now VTimeInSec) VTimeInSec

func (f Freq) NextTick(now VTimeInSec) VTimeInSec

The relationship between ThisTick and NextTick functions.

:::note[What is the drawback of defining time and frequency as floating point numbers.] A: Since floating point calculation is not precise, some times it is difficult to determine if you are at or slightly before/after a clock cycle. This forces us to use a trick to calculate NextTick, using cycle := math.Floor(math.Round(float64(now)10float64(f)) / 10). This adds computational burden and is still not fully safe. Without this trick, NextTick` may return current time, making the whole simulation not moving forward.

:::

Events

In Akita, an event is an action to happen in the future. Events do not have durations. So the action of an event happens instantaneously.

An event has two mandatory properties, the time and the handler. Both fields are immutable. Those fields can only be assigned when the event initiates and cannot be updated afterward.

The definition of the Event interface is defined below. We will explain the IsSecondary function later.

// An Event is something going to happen in the future.

type Event interface {

// Return the time that the event should happen

Time() VTimeInSec

// Returns the handler that should handle the event

Handler() Handler

// IsSecondary tells if the event is a secondary event. Secondary event are

// handled after all same-time primary events are handled.

IsSecondary() bool

}

Simulator developers can define their own Event structs. Other than the time and handler properties, simulator developers can associate extra information with an event.

The handler knows what will happen when the event take place. The handler is a very simple interface (see the code below). Akita mainly rely on simulator developers to define the action that an action trigger.

type Handler interface {

Handle(e Event) error

}

A: A type of event may have different behavior according to who is the handler. For example, TickEvent can be pretty much handled by most of the hardware components, but every component has its own behavior. Having two different entities decouples the data (event and its associated information) and action (handler).

Event-Driven Simulation Engine

Since we have defined event, a simulation can be considered as replaying a list of events in chronological order. Such a player is called an event-driven simulation engine, or engine for short. The engine maintains a queue of events and triggers events one by one.

Central to the engine interface are two functions named Schedule and Run. Schedule registers an event to be triggered in the future. Run triggers all the events (handled by handlers) until no event is left in the event queue. Note that the handlers can schedule future events while handling one event.

Akita supports two implementations of engines, one serial engine and one parallel engine. The serial engine simply maintains an event queue and triggers event in order. We will discuss the parallel engine later.

A: A more simpler type of simulation is called cycle-based simulation, where the engine polls all the components in a simulator to update their states in every cycle. Cycle-based simulation is typically slower than cycle-based simulation. This is mainly because it cannot fast forward useless simulations. For example, it a memory controller takes 1000 cycles to handle a request, event-driven simulation can skip the 999 cycles in between and jump to the end. But cycle-based simulations has to tick all the cycles. Additionally, cycle-based simulations have challenges handling systems with multiple frequency domains. Therefore, Akita uses event-driven simulation.

A Simple Event-Driven Simulation Example

Let’s show how to use the event system with a simple simulation. Suppose we have one small cell at the beginning. It will split at a random time between 1 - 2 second. After that, each cell will also wait for a random time between 1 - 2 seconds before the next split. We want to count the number of bacteria at the 10th second.

The first step is to create an event. The event does not carry any extra information other than the time and the handler. Let’s make it a primary event by always returning false in the IsSecondary function. We will discuss what is secondary events later.

type splitEvent struct {

time sim.VTimeInSec

handler sim.Handler

}

func (e splitEvent) Time() sim.VTimeInSec {

return e.time

}

func (e splitEvent) Handler() sim.Handler {

return e.handler

}

func (e splitEvent) IsSecondary() bool {

return false

}

Then, we need to define the action associated with a split event. We can define the action in the handle method. In this example, we will increase the number of cell by 1 (one cell becomes two).

type handler struct {

count int

}

func (h *handler) Handle(e sim.Event) error {

h.count += 1

h.scheduleNextSplitEvent(e.Time())

h.scheduleNextSplitEvent(e.Time())

return nil

}

func (h *handler) scheduleNextSplitEvent(now sim.VTimeInSec) {

timeToSplitLeft := sim.VTimeInSec(randGen.Float64() + 1)

nextEvt := splitEvent{

time: now + timeToSplitLeft,

handler: h,

}

if nextEvt.time < endTime {

engine.Schedule(nextEvt)

}

}

When a handler handles an event, it can schedule future events. In our example, one cell becomes two when one event is handled. And we schedule the 2 future split events if the events will happen before the 10th second.

Finally, we put the code together in the main program.

func Example_cellSplit() {

randGen = rand.New(rand.NewSource(0))

engine = sim.NewSerialEngine()

h := handler{

count: 1,

}

firstEvtTime := sim.VTimeInSec(randGen.Float64() + 1)

firstEvt := splitEvent{

time: firstEvtTime,

handler: &h,

}

engine.Schedule(firstEvt)

engine.Run()

fmt.Printf("Cell count at time %.0f: %d\n", endTime, h.count)

// Output:

// Cell count at time 10: 75

}

In the example's main function, we first create a serial engine and a handler. We then schedule the first split event to kick-start the whole simulation. The simulation runs with engine.Run(). After the Run function returns, all the events have been triggered and simulation is completed. Finally, in the last line of the function, we print the total number of bacteria.

Parallel Simulation

Digital circuits intrinsically execute in parallel. This is because each circuit part can only access its input and output registers in a cycle. In other words, if we can isolate the input and output of the simulator components, we can also simulate them in parallel with multiple cores.

Akita provides a ParallelEngine to support parallel simulation. The ParallelEngine follows the exact same interface as the serial engine. Therefore, develops of event handlers should almost never need to consider parallel simulation.

Determining if the ParalllelEngine or the SimulationEngine should be used fully depends on the simulation configuration. See the following code for how we create either aSerialEngine or a ParallelEngine. This is the only place we need to differentiate if the serial or the parallel engine should be used.

var engine sim.Engine

if b.useParallelEngine {

engine = sim.NewParallelEngine()

} else {

engine = sim.NewSerialEngine()

}

A: No. Since parallel execution is naturally non-deterministic, parallel simulation will also not create deterministic execution results.

So how the ParallelEngine is implemented. Here, we want to explain a few key point in the implementation.

The principle of the parallel execution is that only same-time events can be executed in parallel. We call the events that are scheduled at the same time a round. The ParallelEngine first identify the time of the next round and triggers the events in the next round.

We use one go routine to handle one event. This is a debatable solution. Another solution is to create a fixed number of goroutines that serve as workers and use go channels to dispatch the events. However, we do not find much performance differences. Therefore, we use the simple, one event per goroutine, solution.

Another concern is that the queue can be a major performance bottleneck due to locking requirement. At the beginning of each round, we trigger events from the queue. While it is triggering, we cannot allow future events to be added to the event queue to prevent race conditions. However, a major part of the event handling is to schedule future events. Then, all these goroutines will have to wait until the queue finishes dispatching.

To alleviate this problem, we create a multi-queue design. The ParallelEngine maintains many queues (we set to the number of cores of the system, defined by GOMAXPROCS environment variable). Events are distributed in all these queues, when one queue is done with dispatching, it will be returned to the pool of available queues. This multi-queue design can reduces the blocking latency as later executed events can easily find earlier queues to schedule future events.

Summary

As demonstrate in the example above, Akita defines a minimalistic framework to manage time within the simulation. With a few key concepts including virtual time, frequency, event, handler, and engine, users can already define interesting simulations.